The Mysterious, Cyclical Bluefish

Turning back time to the '60s, when bluefish were scarce, and a 4-pound chopper was an impressive catch.

Back then, even without the internet and cell phones, information traveled swiftly, especially if you were a member of a select group of watermen.

“Ted Hurley was pulling his pots off Hog Island Light last night and saw bluefish busting on bait. One of the other lobster boats out there caught one about 3-pounds on a tin squid. See what you can scratch up in the lockers and in that old tackle box upstairs.”

The boathouse caretaker was up for an adventure that caused my heart to skip a beat. Bluefish! Although I had heard stories about razor-toothed chopping machines, I had never seen a live one, never mind attempted to catch one. One old-timer, who actually lost the tip of his right index finger in a milling machine claimed it was a big bluefish that jumped up from the deck and bit it off. Blues were described as vicious predators that killed for sheer pleasure, and once full, they regurgitated their stomach contents and commenced killing all over again. They had a reputation for jumping, cutting lines, and being too speedy for the conventional tackle and handlines of the day.

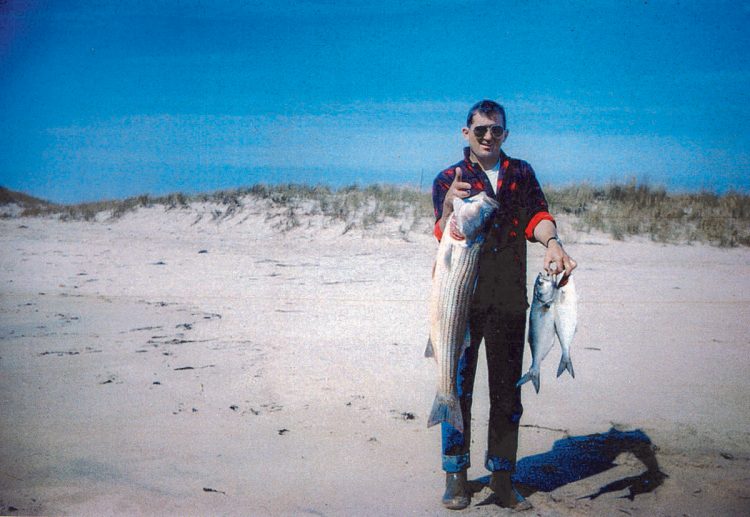

[Submit your fish photos using the Instagram hashtag #OnTheWaterMagazine, or email them to feedback@onthewater.com]

I was to learn firsthand that most of those tall tales were true – a 5-pound blue fought harder and was more difficult to land than a 10-pound striper. With one New Jersey-manufactured tin dressed with a single bucktail hook and two illegitimate lead copies, the caretaker, several friends, and I sailed from the boathouse out of the river and under the span of the Mount Hope Bridge into lower Narragansett Bay. We were afraid that with news of bluefish in the area, there might be too many boats around, but there was not a single hull in sight. After 20 minutes of riding around without a sighting, George, ever jealous of the old man’s popularity, couldn’t resist giving him a jab.

“Not another damn boat in sight. Your lobsterman friend got you to bite on a rumor, hook, line and sinker.” Just as the caretaker was about to issue a fiery retort, Tommy gave a shout. “Fish breaking along the Portsmouth shore, right in front of the nun’s summer retreat.” Sure enough, I turned and saw terns and gulls circling and diving into a melee created by the feeding fish. The old man told Tommy to get a pair of handlines ready as he pushed the old barge as fast as she could go in the direction of the action. By the time we got there, the fish had sounded and showed up in almost exactly the place we had just vacated. After this scenario repeated itself, the old man ordered the lines left in the water and we started trolling.

No sooner had both lines been dropped 75 yards astern when Harold let out a whoop. He reared back on the line and I saw my first bluefish go airborne. Harold hauled, but not fast enough as the fish swam toward the boat, created slack in the line, jumped, and spit the hook. An incredulous Harold took a merciless razzing.

Two more men hooked fish with similar results before we got one to the boat, but upon lifting it, the hook tore out of its mouth and it fell back into the water.

“Give the kid one of those darn lines and see if he can change our luck,” ordered the caretaker, but I deferred to the adults. I was no match for those acrobatic fish and knew exactly what would happen to me after the way they castigated Harold.

That was the night I saw my first live bluefish, though I didn’t get to see one flipping on deck during that trip. Ten years later, on a sultry July morning in 1963, I was carefully negotiating the Sakonnet boulder fields with my friend, Paul Capone, aboard. There were several school stripers up to 8-pounds in the box that had been fooled by Atom Striper Swipers. I cast into a reef spilling white water and responded to a vicious strike. At the set, the fish leaped from the water and violently shook its head. The single-hook bucktail had a firm purchase in the corner of its mouth, and after several more leaps and runs at the boat, the blue came alongside, and I lifted it into the cockpit.

I had decades of experience with every native and migratory species that routinely visited our waters, but I had never seen anything jump, flip, and spew more blood than that little bluefish did. I threw my hand towel over it and lifted it up by the tail to avoid the swinging plug and sharp teeth. I then used my belt knife to rip the tissue under the apex of its gills to bleed it out before putting it on ice.

That day marked the beginning of one of the greatest recoveries of any species I have ever fished for, though it has been either feast or famine. That year, I won a Schaefer trophy for the largest bluefish taken in our club’s contest – with a 4-pound chopper. My friend, Charlie Cinto, took his first blue off the beach at Provincetown and said he was more excited about those small yellow-eyed devils than the four keeper stripers he caught that same weekend. Those first blues brought 25 cents a pound, a nickel more than the stripers we sold at Drapes Seafood.

It was the beginning of a great run of bluefish. Over the next 20 years, those fast-growing fish became the most sought-after local species, with 18- to 20-pound specimens fairly common. I immediately developed an appreciation for one of the fastest and hardest-fighting species that swims. Although some people might complain about their taste, I blame that on poor handling. I enjoy blues on the grill, and one of my favorite snacks or spreads is smoked bluefish prepared by a friend who uses the freshest and firmest fish I can provide. Mine do not sit in the sun in a tote on deck, but in a cooler with a saltwater slurry of cubed ice.

However, a few years after those first blues arrived, I became engaged in a love/hate relationship with this unpredictable species that started when they made their appearance in lower Narragansett Bay. Their first intrusion was during what we referred to as herring season.

It was May 13, at exactly 9:15 a.m., when I called my partner Fred on the VHF and told him I had landed two bass in the 18-to-20 pound class at Providence Point off Prudence Island. While he headed over in his Whaler, I netted a fresh bait out of the livewell and noted there were only six more river herring still swimming. As anyone who has slipped and gotten dunked in the pre-dawn hours while netting herring knows, those baits were worth the effort it took to collect them because every one of them was worth a bass.

I hooked the bait through the nose, let out 125 feet of Monel line, and began my pass. I was almost to the hump when the bait began to flutter and surface, indicating there was a predator sizing it up. Just then, a fish struck, but wasn’t hooked. What happened? I continued my pass, now trolling a lighter bait that showed no signs of life, when there was a second strike, also without a take. I began to race the bait back until it broke the surface; right behind it was the biggest blue I had ever seen in the bay. It sounded, then came up under the bait, swallowing the remains of its head and gills. I set the hook, which brought about a leap and some of the most exciting tail-walking I had ever seen, other than the time I hooked a skillie (white marlin) south of Nomans Island.

The same drag that had subdued a pair of 20-pound-class stripers couldn’t even slow that blue’s first run. Then, it abruptly turned and headed directly toward the boat. Despite cranking my dependable Penn 113 as fast as I could, I couldn’t take up the slack. The fish saw the hull, put on the brakes, and started to dive when I locked down the drag and lifted. It turned back toward me, jumped, and crashed into the side of the hull as its teeth finally severed the 50-pound-test monofilament leader.

Over the next few decades, I learned that the first blues to invade our bays are long, lean alligators on search-and-destroy missions. They are not satisfied with chopping the tail off your hard-won live baits; they keep chopping past the hook and into your leader.

Blues are usually “here and there,” but for the last few seasons, they have been “there” rather than “here” most of the time. One disturbing sign of their population decline, at least to me, is that for the last two seasons, the only blues we found were large. I also recall the end of the 1970s when small stripers were rare and noticeably big fish were the norm. I hope that this similarity is not a duplication of that period of the striper’s catastrophic history. We know where stripers’ inshore spawning grounds are, and with regulation and sacrifice, we have had some control over their recovery. That might not be the case with bluefish, which spawn offshore and depend on tidal currents and favorable winds to push their offspring into nursery areas in our rivers and bays.

With a three-fish-daily bag limit for private fishermen this year, I will need a two-day supply to make it worthwhile to concoct a brine and crank up the smoker. However, I can assure you that every one of those choppers will be very much appreciated from the ocean to the dinner table.

Related Content

Article: The World’s Best Bluefish Recipe

5 on “The Mysterious, Cyclical Bluefish”

-

Ken Didn’t give it much thought until I read your story . I fish often , yet I did not catch 1 bluefish all season . Usually, they are consuming all of my rubber baits. November 22,2020

-

Paul Martin I’ve caught blues up past the Berkley Bridge, São Miguel, Azores, and here in Galveston.

-

John Do you have a commercial permit to sell fish to Drakes seafood?

I’m pretty sure sale of striped bass is illegal.

Drakes seafood should be questioned and fined for buying seafood from a non licensed seller.

-

Wendelin J Giebel “ In estimating the importance of menhaden to the United States, it should be borne in mind that its absence would probably reduce all our other fisheries to at least one forth their present extent”

G.Brown Goode. A Short Biography of Menhaden 1882

Rhodesia Island Printing Company

We have fished the Atlantic menhaden down to maybe 2% of its unfished biomass or Bzero. The mathematical model and maximum sustainable yield claptrap is destroying the east coasts food web. This was understood in the 1800’s . -

Driscodre I caught about 10 blue fish last season. They were everywhere in nahant and boston harbor big and small.

Leave a Reply